Photography by Mathilde Hiley

Produced over a year ago in collaboration with photographer Mathilde Hiley, this photo essay immerses us in the atypical world of Josh Raiffe and his strikingly unconventional bag-objects. While spending the summer in Brooklyn, the photographer delved into the behind-the-scenes process of their creation. After the shoot, the editorial team sat down with the designer to learn more about his nonconformist approach and what this fashion accessory truly represents in his eyes.

Before getting into the subject, could you tell us a little bit about yourself and your background? How did your interest in glass come about?

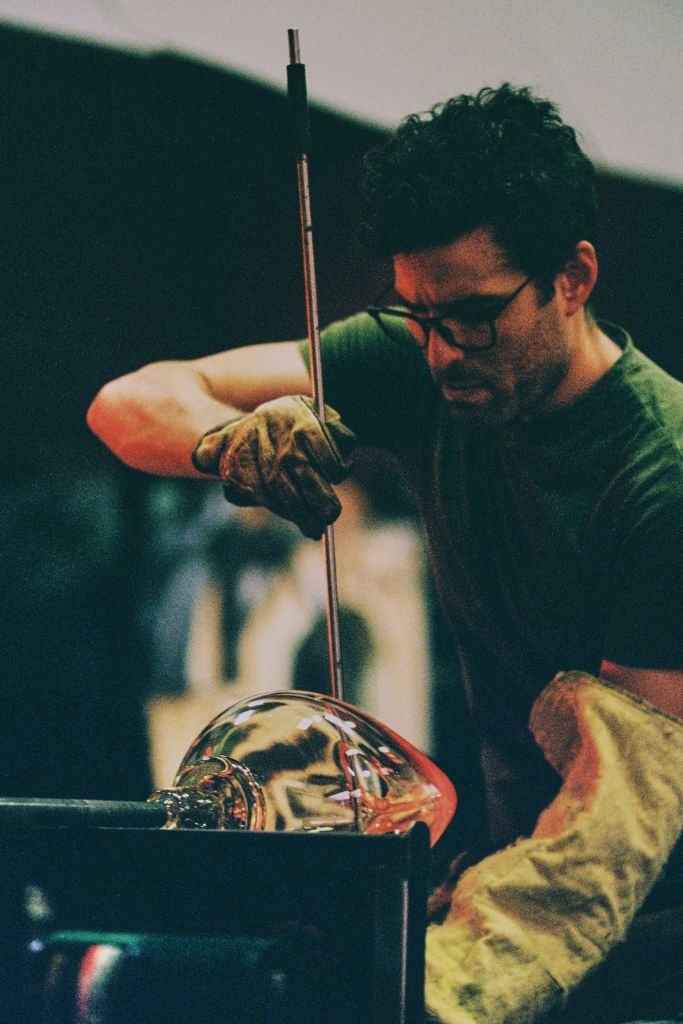

Well, I’ve always been an artist. Ever since I was a little child, my mom really fostered in me and all my siblings a deep love for the arts. We would have art days. She would pay for art classes. And yeah, I’ve always loved art, and so I went to art school, Tyler School of Art, mostly for sculpture. I’ve always been a three-dimensional thinker, and I did a lot of clay and stone carving, and I found their glass program amazing. I really fell in love with blowing glass at Tyler School of Art, so that’s really how I found glass.

How did you come up with the idea of creating these stunning glass accessories? What is it about glass that makes your creations so special?

That’s an interesting question. I guess the question is really about where the inspiration comes from. I’d say life. Everywhere. I think it’s important to be an interested person, not necessarily an interesting one, but someone interested in lots of different things. I love cooking, board games, sci-fi and fantasy… I’m a hobbyist.

I love picking up new hobbies. And I think that’s key: some artists, like glassblowers, only focus on their medium, but I think it’s more compelling when you bring something from a completely different field. Like if you were an astrophysicist and then became a glassblower, that cross-pollination brings richness. So for me, it’s all about staying curious and pulling from lots of places for inspiration.

Your glass bags arouse intrigue. At first glance, they seem like delicate, untouchable treasures. However, when you hold them in your hand, a kind of bond is created with the user. Can your bags be considered works of art? Are they meant to be used or simply admired?

They’re mostly meant to be used. I don’t let functionality dictate what I create, but I do often design with ergonomics, lightness, and practicality in mind. That said, sometimes I completely abandon usability for the sake of design and that’s okay. As for whether they’re art or not, that’s up to interpretation.

I think something becomes “art” when it carries intellectual or emotional value, when it has meaning, a story, or evokes feeling. But I don’t worry too much about defining my own work. I just make what I want to make, and people can call it what they want.

« I refer to my bags as proactive designs. » What does that mean?

I’ll be honest, I don’t remember ever saying that, but I like the phrase. I guess I’ll pass on that question since it doesn’t ring a bell. But it does sound nice.

We often say that a bag reflects the image we wish to convey and reveals a part of our personality. Do you share this view? How do you approach the design process so that each model stands out?

Yes, I do kind of agree. Everything you wear reflects who you are in that specific moment, based on what you’re doing and how you feel. We’ve all had that moment where an outfit feels off it’s just not “you.” And other times, you put something on and it feels perfect. So yes, bags and clothes are definitely a form of expression. As for my process, I don’t really worry about making each model different. I have more ideas than I can handle, sometimes it’s overwhelming.

The real challenge is not coming up with ideas, but deciding which ones are actually worth making. Sometimes I’ll be super excited about one and then realize after making it that it just wasn’t a good idea. So a lot of my process is about editing.

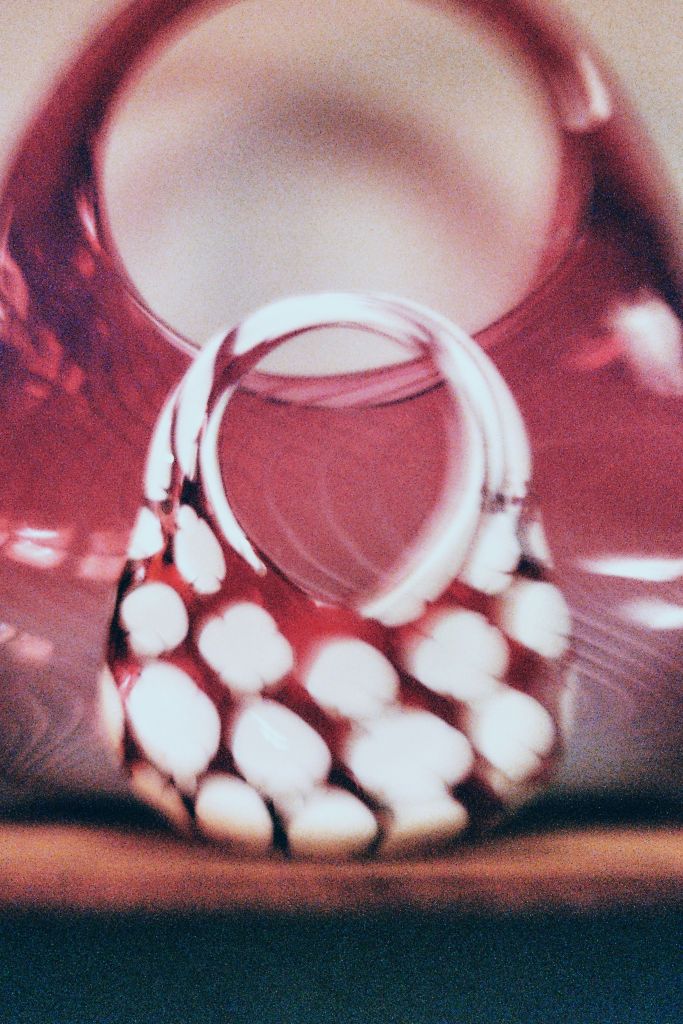

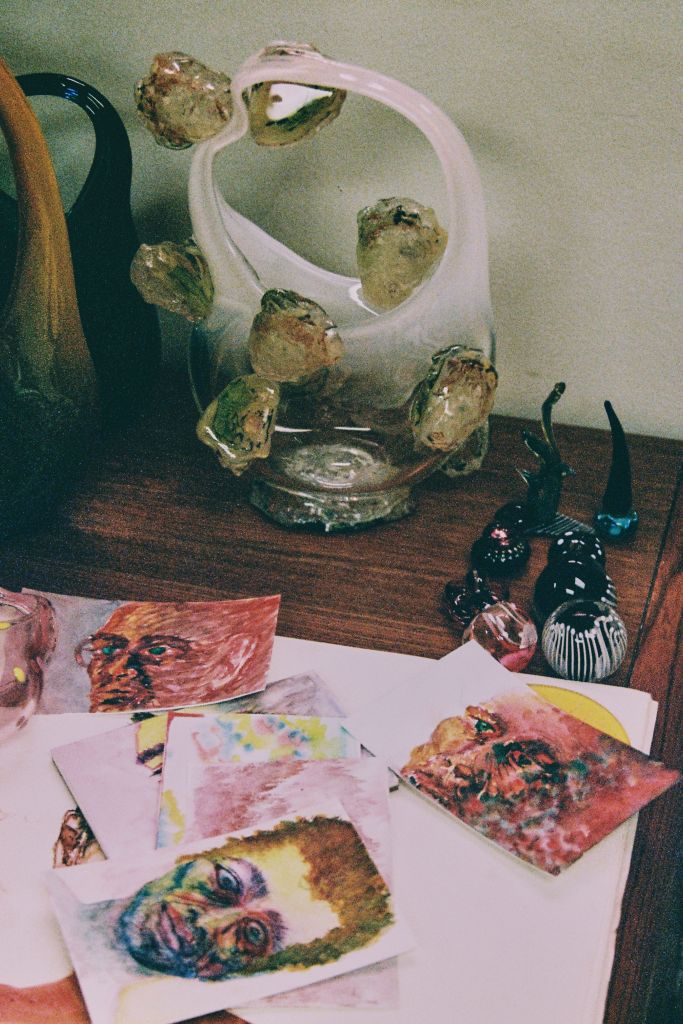

Whether it’s oysters, golden spikes, water droplets, or zebra stripes, every detail that adorns your glass pieces contributes to their uniqueness. What motivates you to design items this way?

Each design element has its own origin. The oysters came from a collaboration with my friend Michael Potetcha he was already making glass oysters, and I loved them. I asked if we could do a collab and he agreed. The golden spikes were an idea I sketched over and over.

I wanted them to be actual gold not gold glass, not gold-colored glass. It only became possible when a jewelry company offered to help. As for the water droplets, zebra stripes… sometimes they come from sketches, sometimes from just playing around in the studio and seeing what emerges.

What are the sources of inspiration and references that motivate your artistic approach? How would you define your role in today’s design landscape?

I think I already talked about my sources of inspiration. As for my role, I think I exist in a lot of different spaces. Some galleries show my work as sculpture, some fashion runways show it as wearable art, and some design galleries also feature it. I really like that. I’m not trying to fit into a category, and I don’t mind if other people define it differently. I think my work bridges a lot of worlds, and I want to keep expanding into even more.

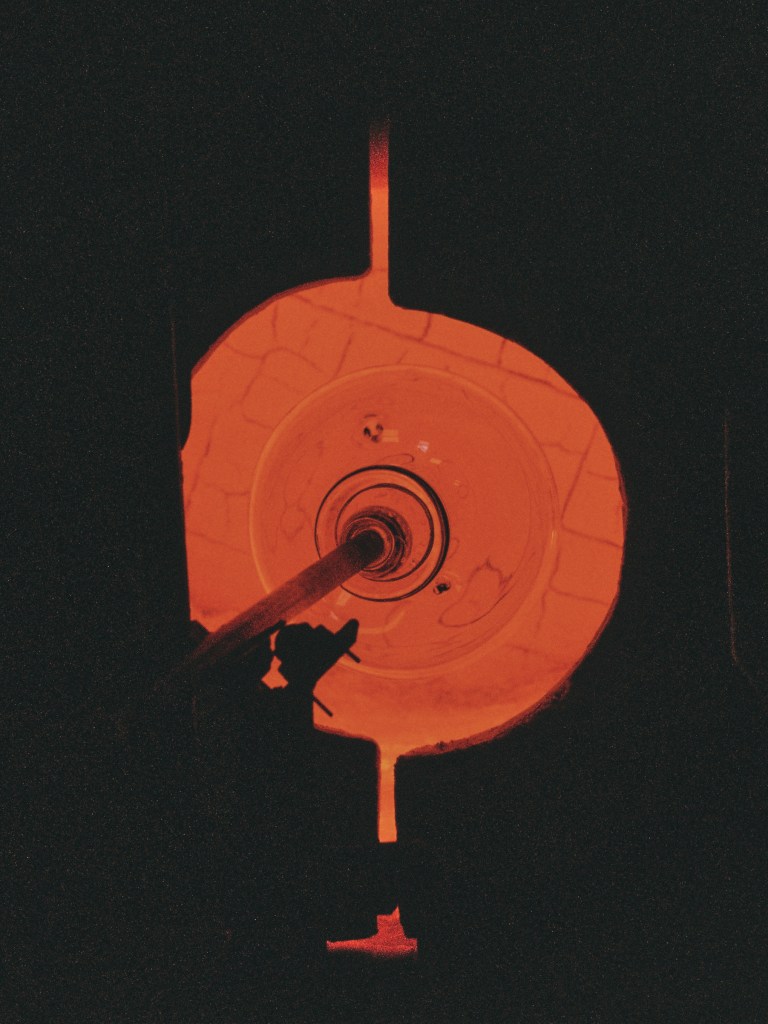

Looking at your work in the studio, it’s obvious you have total control over the material. How do you control and shape it to suit your artistic vision?

Blowing glass is hard. It takes years of training and a lot of cuts and burns. The downside of being so skilled with glass is that I tend to try to make everything out of it, even when another material might be better.

Like with the golden spikes, I wanted them in glass first, but it just didn’t work. Eventually I found a better material. But yes, glassblowing is my strongest skill, it’s the best tool in my toolbox.

Unusual is generally defined as something that departs from the ordinary. Do you consider the production of your glass bags to be unconventional?

Definitely. The process is unusual, but not unprecedented. Venetians were making glass bags as far back as the 1960s, and even earlier in 1890s South Jersey, there was a trend of glass baskets that are kind of bag-like. So I’m not the first but I do them my own way. That’s what sets me apart.

As a designer of fashion accessories and a glassblower, you navigate two seemingly opposite worlds. Can you tell us more about this intriguing duality?

I’m definitely a glassblower first. I don’t know a lot about fashion but I love being part of it. I admire the creativity, the mind-blowing designs, the beauty that can move you.

But there’s also a side of fashion I don’t like: the superficiality, the celebrity worship, the toxicity. So there are pros and cons. Still, I don’t pretend to be a fashion expert I just found myself in this world, kind of by accident.

Now we’re going to ask you to use your imagination. Can you describe the most unusual creation you’d like to make?

That’s a fun one. I’ll tell you about three ideas I’m working on right now not super wild, but projects I plan to make in the next couple of months. First, the grandma bag: it’s a stack of three bags, each one holding up the next like generations supporting each other, passing down wisdom, love, DNA.

Second, a nuts-and-bolts bag, inspired by the golden spikes. But instead of spikes, it’ll have bolts jutting out. They could be gold, chrome, or silver-plated. It’ll have a street, construction vibe very grungy. I think it would look amazing in clear glass. Third, a neon bag more of a sculpture than a bag. It won’t have any inside space, completely solid, with glowing neon gas inside in a zigzag pattern. It’ll be powered by a bracelet you wear, which holds the battery and transformer. Those are my current ideas. Well, thank you so much. I really liked this, it was a good interview.